|

A Vacancy on the Court | < |

The Senate

I based my decision on a careful review of the nominee's intellectual capacity, his background and training, and his integrity and reputation.

I cannot find a single distinguishing aspect of Mr. Thomas's legal career that would warrant his consideration for the Court.

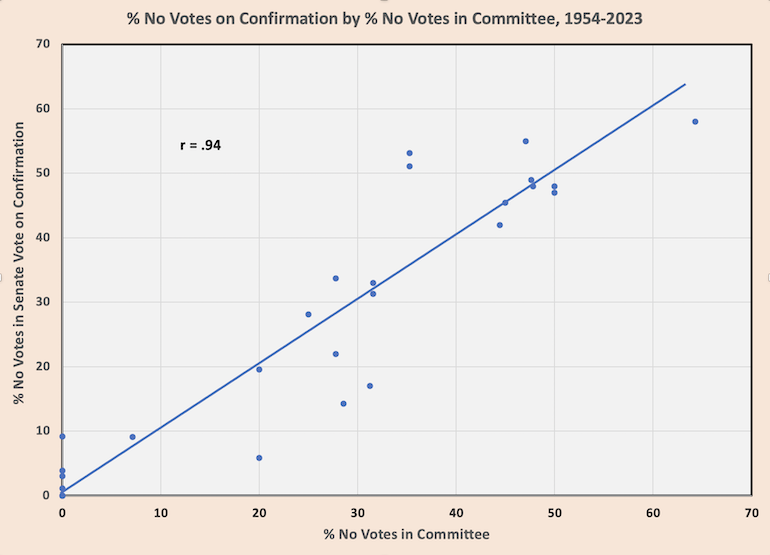

Article 2 Section 2 of the Constitution Advice and ConsentThe Constitution provides a deceptively simple, yet almost obscure, dictate about the Senate's role in confirming Supreme Court justices - "advice and consent". "Consent" means that a majority of votes cast must favor confirmation in order for the appointment to occur. However, there isn't an opportunity for the Senate to advise the President on an appointment, unless he seeks out the opinion of a few key senators or perhaps senators offer their unsolicited opinions. Why? Because George Washington wanted it that way. When you're first, you get to establish several precedents, and one that Washington set was that the President would send nominations in writing to the Senate and that the Senate should respond in kind. There would be no meetings between the President and the Senate to determine who should be appointed. In Washington's view, the President could nominate anyone he wished and he didn't have to justify his reasons to the Senate. On the other hand, he recognized that the Senate had the right to reject his nominees without giving their reasons for doing so. Senate ProcedureThe Senate Judiciary Committee Despite the fact that certain procedures for the Senate's advice and consent function were established the first time George Washington and the Senate interacted on nominations, other procedures have only come into being more recently. Since 1949, when the Senate receives a Supreme Court nomination from the president, the nomination is referred to the Senate Judiciary Committee for hearings. Until then, hearings were held only sporadically, usually in an instance where some controversy had arisen regarding a nomination. The testimony of the nominee, which now highlights the Committee hearings, has been a regular feature only since 1955. And only since 1981 have we been able to watch the hearings live. Recommendations The Committee is expected to make a recommendation to the Senate, whether that recommendation be to confirm or to reject. That too has not always been the case. A common method of quashing nominations to the lower federal courts is simply for the Committee not to report on the nomination, to kill it in committee. That is unlikely to happen with a Supreme Court nomination today, although in the case of President Obama's nomination of Merrick Garland in March 2016, Senate Majority leader McConell never even forwarded the nomination to the Committee for consideration. Even if the majority of the Committee opposes the nominee, they likely will report that fact to the full Senate as a recommendation to reject the nomination. Upon receiving the recommendation of the Judiciary Committee, the Senate leadership will schedule a debate and a vote on the nomination. In a non-controversial nomination, like that of Ginzburg or Breyer, only a few senators will rise to praise the nominee before proceeding to the vote. In a more controversial nomination, more senators will rise in support of or opposition to the nominee. The Senate Confirmation VoteImpact of the Committee Vote The vote in the Senate will look a lot like the vote in the Judiciary Committee, in part because the Committee tends to be reasonably representative of the whole Senate. In addition, the Committee vote cues senators outside the Committee how to vote. The table below shows the relationship between Committee vote and the Senate vote. The percentage No vote in the Committee has an almost one-to-one relationship to the percentage vote in the Senate, keeping in mind that each committee member constitutes 5% or more of the Committee, so any predictions will have a certain amount of error. When all 11 Committee Democrats voted against Barrett in 2020, the 12 Republicans voting to confirm, the 48% Committee No votes predicted 47% of the Senate votes would be No. The actual No votes were 48%.

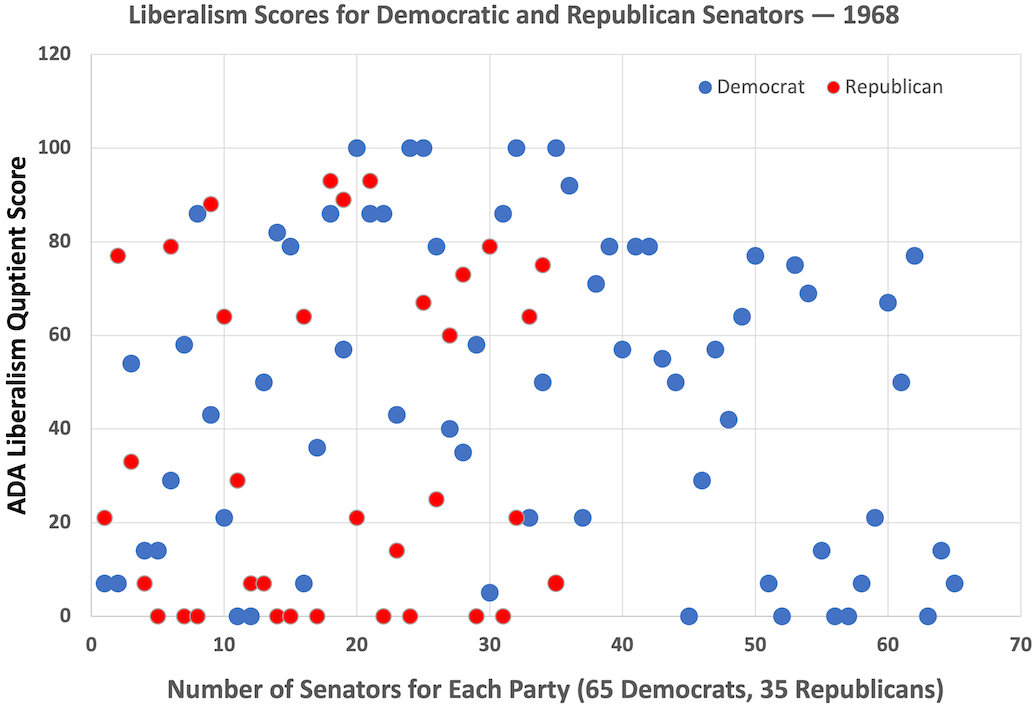

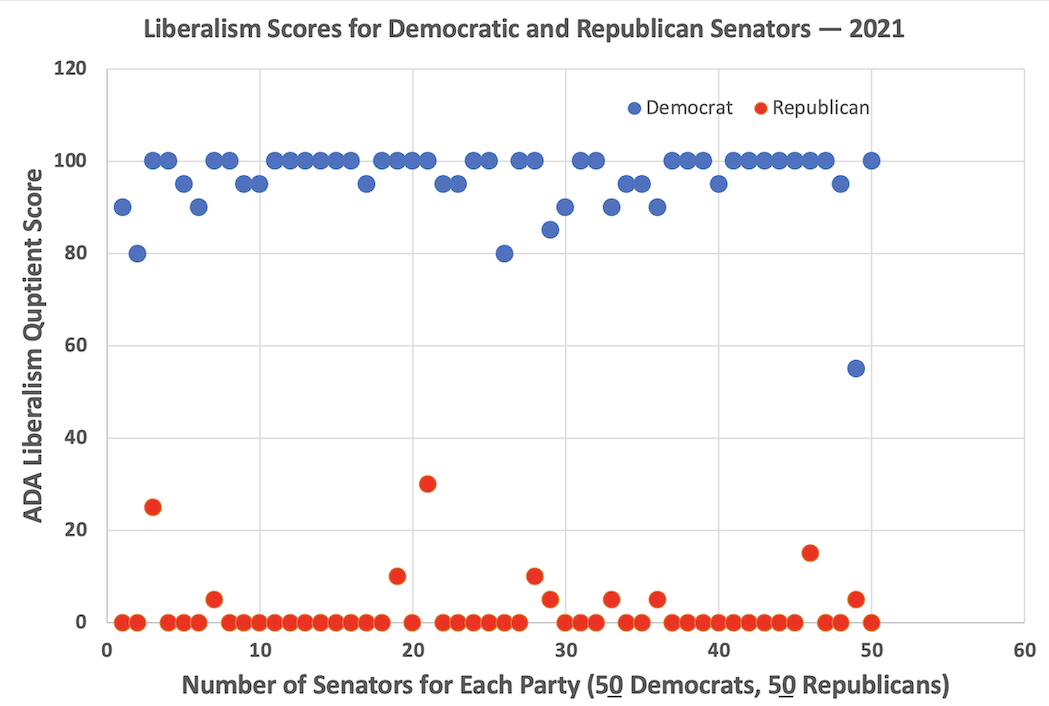

Partisanship and Ideology Perhaps the most notable feature of American politics over the past 60 years is the alignment of political party and ideology. It has dramatically changed how our political system operates, the appointment and confirmation process included. In the 1968 chart below, we see both Democratic and Republican senators were arrayed across the ideological spectrum, as measured by the Americans for Democratic Action (ADA) liberalism quotient, based on voting in select issues for that year. By 2021, only one senator fell in the middle range of the measure, Democrat Joe Manchin of West Virginia. In 1968, 51 senators fell between 20 and 80 on the measure. By 2021, only 3 senators occupied that middle ground, 2 more having scores of 80.

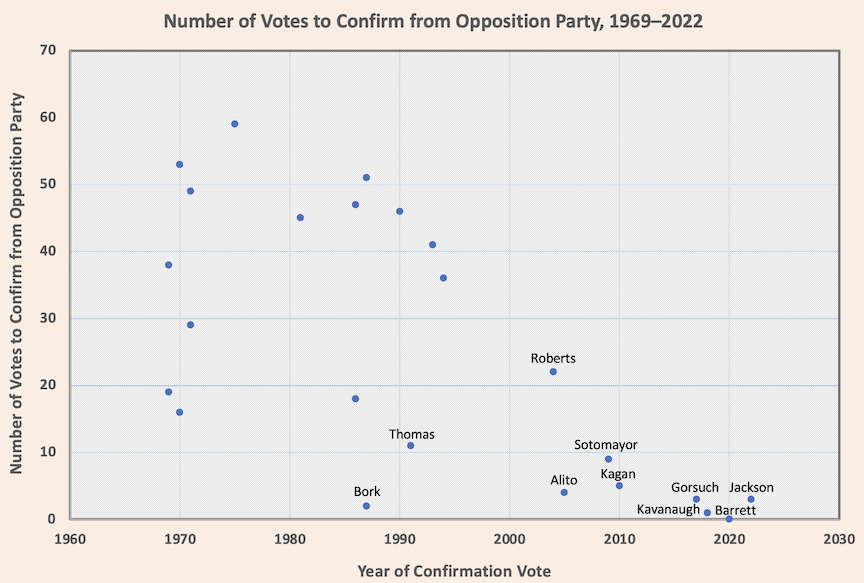

The impact of alignment is clearly discernible in the table reporting the number of votes to confirm Supreme Court nominees cast by members of the party in opposition to the president. Members of the president's own party typically support confirmation, there being only four instances of nonsupport on any of the current justices. Before the alignment of ideology and party, that was not always the case. Fourteen of the 15 votes against the confirmation of Thurgood Marshall in 1967 came from President Johnson's Democratic party, all Southern conservatives, the fifteenth being the first Democratic to Republican switch, Strom Thurmond of South Carolina. Five of the six Republicans opposing the confirmation of Robert Bork in 1987 had liberalism scores ranging from 60 to 85, no Republican senator in the 21st century having anything close to a score that high.

The effect of coalescing ideological and partisan interests is clearly seen in the inability of any nominee in the 21st century, other than Chief Justice Roberts, to gain double- digit support from the opposition party. In 2020, Amy Coney Barrett became the first nominee not receiving a single vote to confirm from the opposition party since the back-to-back nominees of President Grant in 1869 and 70. In a Senate fairly evenly split along partisan and ideological lines, every vote counts, and toeing the party line is likely to be the norm in confirmation votes for generations to come. Eliminating the Filibuster for Supreme Court Confirmations In the ordinary course of actions by the Senate, a majority vote determines the outcome of an issue. The Constitution requires a two-thirds vote to approve treaties, remove an impeached official, override a veto, and propose a constitutional amendment. Since its inception, the Senate has adhered to an ethic of unlimited debate, which has been famously used to prevent motions from coming to a vote. In 1917, President Wilson successfully prevailed upon the Senate to establish a rule (Rule XXII) permitting debate to be cut-off, a procedure known as cloture. Rule XXII also establishes a two-thirds vote for amending the Senate Rules. Initially, the vote needed for cloture was two-thirds, but that was changed in 1975 to three-fifths. Because of their lifetime tenure, judicial nominees have been particularly susceptible to delaying tactics by the minority Senate party when the presidency is held by the majority, although a formal filibuster that brought forward a cloture vote has occurred only once. In 1968, President Johnson's nominnee for Chief Justice, Abe Fortas, was successfully filibustered by the Senate Republicans, the vote to cut off debate fell far short of the needed two-thirds, 47-45. The potential for filibusters existed with three other nominations, that of Clarence Thomas (1991), Samuel Alito (2006), and Neil Gorsuch (2017). In the first two instances, a sufficient number of Democrats demurred at the prospect, and the nominees were confirmed by 52-48 and 58-42 votes respectively. The nomination of Neil Gorsuch by President Trump, on the other hand, especially galled the Democrats because the Republican Senate had refused to consider President Obama's March 2016 nomination of Merrick Garland to replace Justice Scalia, the intellectual leader of the conservative bloc. The 52-48 Republican advantage was 8 votes short of what would be needed to close out a Democratic filibuster. The Democrats did indeed initiate the filibuster, and the Republican effort to invoke cloture failed in a 55-45 vote. Not to be denied, the Republicans pursued what was referred to as the "nuclear option," doing away with the filibuster option for Supreme Court justice confirmation votes. A parliamentary maneuver permitted the majority to bypass the regular two-thirds vote rule change, effecting the change with only a simple majority vote, and the Republicans prevailed in a straight-line party vote of 52-48. Gorsuch was then confirmed by a 54-45 vote. All subsequent confirmations were by narrow margins well below the former three-fifths required to overcome any filibuster (Kavanaugh: 50-48, Barrett: 52-48, Jackson: 53-47). The three-fifths rule remains in effect for the regular legislative process, serving as an effective tool for the minority to block legislation sought by the majority. Both parties continue to live with it when in the majority realizing its usefulness when they inevitably will be the minority party. For a list and breakdown of confiirmation votes of Supreme Court nominees, go to

|