The traditional conservative/liberal dichotomy that dominates descriptions of American politics oversimplifies and thus obscures the richness of the nation's political landscape. And while this website acquiesces to the false dichotomy in describing the voting behavior of justices, it does so to remain conversant with and relevant to the dominant political discourse. Nonetheless, what follows is a description of a simple but richer perspective on ideology that helps one understand what it means to be conservative or liberal and why those labels can be confusing.

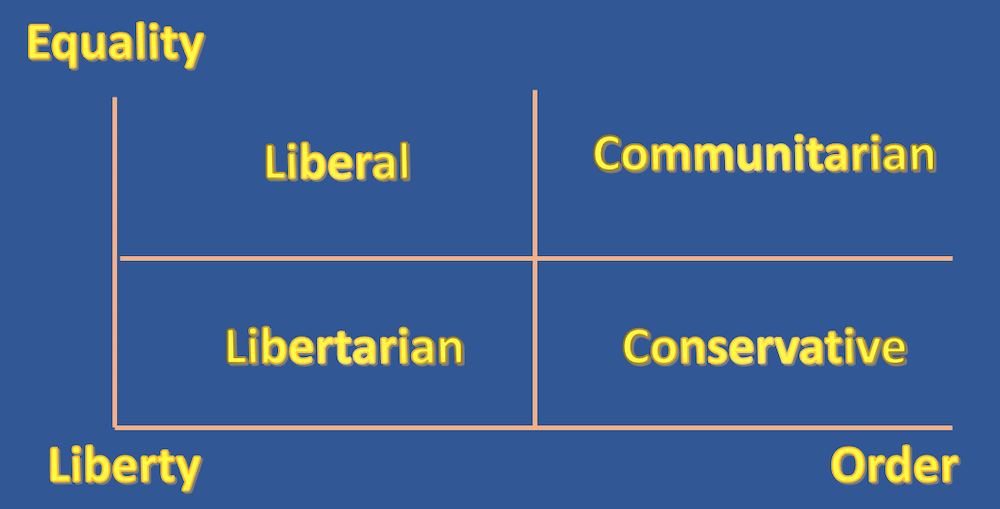

The political ideology matrix on the right is adapted from Kenneth Janda et al. text, The Challenge of Democracy (Cengage Learning, 2022), p. 24. They assert that the original dilemma confronting political philosophers during the formative period of our new nation was a tension between freedom and order. My "take" on this asserts that classical liberalism affirmed the value of the individual and posited that individual liberty and freedom were needed for the full development of the self. That value was embodied in the Declaration of Independence's quest for "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness." The classical conservative response to liberalism was less optimistic about human nature and saw a much greater need for order in society, presumably secured by a government that supported traditional values of the culture. In short, liberals were more likely to value liberty over order; conservatives favored order over liberty.

The American constitution is an interesting blend of that classical liberalism expressed by the Declaration of Independence and the conservative attempt to bring order and a sense of national community to the states. The Bill of Rights reflected the framers effort to insure both liberty and order in a new nation. The result is a constitution that even today pits issues of liberty against order, liberals against conservatives.

The industrial revolution in the 19th century profoundly changed the social and political order. Some liberals began to see their end-goal of the self-actualized individual obstructed by a laissez-faire economic and political system that stifled liberty. The people, for all their presumed political liberty, were not really free at all. They could not make choices about their lives because they were constrained by economic forces beyond their control. These liberals began to argue that social equality was needed if the political equality envisioned for a democracy was to work and if individuals were going to have opportunities for self-fulfillment. Beginning in the 19th century and increasingly in the 20th, issues that placed liberty and equality in opposition to each other arose (e.g., school desegregation, affirmative action, civil rights). In such issues, many liberals abandoned the classical liberal focus on liberty in favor of an emphasis on equality as being most consistent with their underlying philosophical values. Conservatives, on the other hand, were more likely to see efforts to force equality as social engineering that violated the traditional and natural order. Consequently, they are more likely to favor liberty over equality on issues that fall along that dimension.

The introduction of two dimensions rather than just one to distinguish issues results in a matrix of the type shown above. It creates quadrants that are quite consistent with the American experience. The matrix anticipates individuals who favor liberty over order, just as the liberals do, but who, unlike the liberals, also favor liberty over equality. Such individuals are libertarians, and the Libertarian party in the United States clearly embodies these values. Neither conservative nor liberal, but with the potential of siding with either depending on the issue, by faithfully embracing the same principle (liberty) regardless of the issue, the libertarians are the most single-minded of these four ideologies.

The matrix also suggests one may favor order over liberty, as do the conservatives, while siding with the liberals on issues that pit equality and liberty against each other. In our political history, this perspective characterized the populists of the 19th century. With their strength in agrarian movements of the South and the Midwest and Plains, the populists combined a willingness to accept a strong role for government in the economy and in promoting social and economic equality. At the same time, populism exhibited a strong sense of traditional cultural values and moral absolutism of social conservatism. As used today, however, populism connotes something a little different. In its place, Janda and his colleagues label this quadrant as communitarian, and indeed there is a political movement that uses this label and exemplifies this quadrant.

Supreme Court cases often raise multiple issues that permit different ideological perspectives. Take for example the case of Gonzales v. Oregon (2006), in which the Attorney-General of the United States and the Bush administration attempted to effectively nullify Oregon's assisted-suicide law. Libertarians would oppose any government restrictions on an individual's capacity to make such a personal decision and they would likely also oppose this interposition of the federal government on a law approved by the people of the state of Oregon. Like libertarians, liberals would support the right of the individual to make this personal choice of life or death, although unlike libertarians they would support government controls designed to protect individuals in the making of such a choice. Conservatives would generally oppose assisted-suicide altogether as a violation of the social and religious mores in this nation and would accept government efforts to prevent it. Communitarians would be driven by their own social and religious beliefs and probably oppose the law. However, their equalitarian streak could prompt them to oppose efforts by the federal government to override a law approved by a vote of the people. A cross-cutting issue here is federalism—state versus national authority. However, appeals to federalism are more often used as expedients in support of one's underlying ideological position. In the Oregon case, Scalia, Thomas, and Roberts argued unsuccessfully that federal control trumped the voter-approved state efforts to provide for assisted-suicide. Stevens, Ginsburg, Souter, Breyer, Kennedy, and O'Connor sided with Oregon in putting down the federal conservative challenge.